The world of inspirational speaking is a popular (and lucrative) part of modern culture – particularly in the fields of motivation, success, health, wealth and leadership. People will spend huge sums just to hear the best speakers tell us how we can change our lives for the better. Some of it may indeed be useful, but much of it is just, well, bubblegum.

There is a world of a difference between how persuasive something is, and whether the key messages are in any way true. A very skilled storyteller could easily convince you of something that is factually inaccurate – perhaps even an outright lie – and you would not necessarily know.

Establishing whether something is true takes quite a lot of work, most of it far removed from the world of public speaking and presentation. It’s done in the back rooms, through hard work, testing, studies, experiments, draft publications, criticism, argument, peer review, detailed scrutiny, and most of all – good evidence. It requires specialisation and familiarisation with the field and a readiness to accept that new evidence might upset what is known. It requires expertise – something that the vast majority of us will never have. Nobody can be an expert in everything, so we are all vulnerable to the messages we are given. We even fail in distinguishing proper experts from pretend experts. It’s a minefield.

Fortunately, there is a difference between most pretenders and people who actually know what they are talking about. Where experts are usually tentative, pretenders are certain. Where experts will cite exceptions, pretenders will dismiss them out of hand. Where experts will qualify their remarks, pretenders will have no such qualms.

The best we can do is to recognise the tricks. Here are 5 red flags to be on the look out for.

Anecdote over evidence

Anecdotes are nicely packaged stories designed to support the points being made. While they can be very compelling, they are not considered to be good evidence. Anecdotes can be very subjective (one person’s testimony only) and selective (leaving out details that do not support the point being made). They are lacking in any rigour and ignorant of alternative factors. They can be coloured and adjusted through time and practice. What they are good at is creating a powerful emotional response in an audience. The more perfect the anecdote seems, the more wary we must be.

Style over substance

It’s amazing what we can do nowadays to deliver the perfect message. Presentations can be enhanced through powerful imagery, humour, appeals to emotion and common sense. Music and sound-effects can be used. The colour, the font design, the transitions – it’s all at the fingertips of the skilled presenter to enhance the message. The presenters themselves can use vocal variety, body language and simple stories to get through to us. It’s an art in itself and the more swish it seems, the more we should be looking for the underlying substance. The basis of the presentation is still important – if it’s not there, or justified merely through common sense or “everyone knows this” – our suspicions should be raised.

Too Good to be True

Experts are aware of the many pitfalls in declaring a breakthrough too hastily, so they tend to qualify their arguments, preferring to publicise their small advances rather than one big denouement. Discoveries tend to build up over time, as alternative possibilities are systematically closed off. Often, we are unaware that a great breakthrough has been made because the underlying work was revealed in dribs and drabs. It’s only when we look back that we can see progress. The pretender has no such qualms. To them, their discovery is the best thing since the wheel. The worst of them compare themselves to Newton or Einstein. They have an unshakable belief that they are right, and that their critics are deluded or malign. Seemingly amazing or stunning announcements require a great deal of support to be accepted.

Sciencey Super-words

Many pretenders will abuse the scientific lexicon if they feel it will help their ideas gain legitimacy. We need to be very careful of words like “quantum”, “multiverse”, “laws of attraction”, “neural”, “magnetic”, “epigenetic” and many other words, particularly when they are used in medical or motivational contexts. Similar words we need to be careful about are “organic”, “natural”, “healing”, “chemical”, “genetically modified” and “toxic” – as their impact is often more emotional than factual.

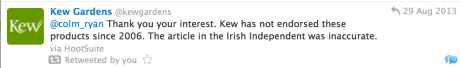

Perfectly Parcelled Evidence

Finally, pretenders love science when they can make it suit their aims. If a scientific study is found, even obliquely, to agree with the message being promoted, you can be certain to see it mentioned as they make their claims. No mention is ever made about whether the study actually supports the points being made, or whether the methodology was poor, or any other study that contradicts the message. We have to be careful, particularly if the message is rather extraordinary. In new fields of study, there may be an enormous debate still raging, where no strong conclusions can yet be made. In older fields, it is likely that the study being mentioned has long been debunked and a consensus reached. A small amount of research on the Internet might tell you more.